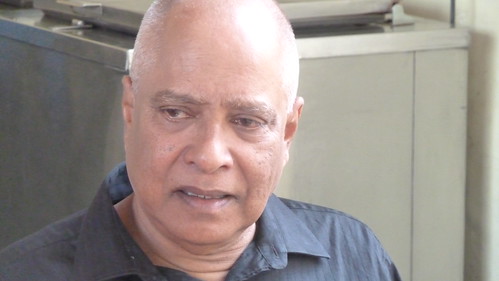

Around two months ago, at the launch of

the Indo-Portuguese historian Teotonio de Souza’s latest book, Eduardo Faleiro,

former Union Cabinet minister and former NRI Commissioner of the Goa

government, argued for imparting primary education in the local language. Excerpts

of his speech were recently published in The

Goan Review (September-October, 2014), and therefore his key arguments are

available for greater scrutiny. Speaking at the launch of Goa Outgrowing Postcolonialism, Faleiro sought to trace a linear

and rather simplistic connection between the violence of colonialism, the

destruction of native culture, and the (purported) contemporary need for

education in the native language(s).

The core of Faleiro’s speech rested on

the understanding that Portuguese colonialism resulted in the destruction of

the Konkani language “almost completely”. Since “[l]anguage is central to

culture”, Faleiro seems to argue that one can undo the damage and alleged humiliation

of colonialism by regaining the pre-colonial glory of native culture. He therefore

suggests that Konkani and Marathi need to be studied at primary level and that

“[t]here is no justification for English as a medium of instruction at the

primary level”. Also, “Konkani should be taught in the Devnagri script as it

will provide access to Marathi and Hindi… [and] Children will learn the romi script

when they learn English”.

While acknowledging the ills of

colonialism, one should be careful not to take the idea of wholesale

destruction under colonialism at face value. Also, how valid is the idea that

the pre-colonial period was a glorious epoch and thus worthy of recovering? For

the problems with such thinking clearly come to the fore when Nagri script is

considered as a way out of the ills of colonialism. The underlying assumption

is that the Nagri script is more ‘Indian’ and hence best suited for the task of

recovering the lost cultural heritage.

Faleiro is not making any new

suggestions as far as the linguistic and cultural realms of Goa go. By making

the argument for the Nagri script, he joins a very long list of largely upper-caste

Nagri protagonists who have thus far ensured the denial of Government

recognition to the Roman script. One can understand why Faleiro is favouring

the Nagri script, as in the worldview that he seems to be drawing upon, the

culture-destroying Portuguese colonialism is where Konkani in the Roman script

had its birth. However, such an understanding fails to take note of the very

real possibility that through the Roman script, written texts (chiefly

Christian literature) were made available to a large mass of people. This access

was not possible prior to missionary intervention because until then it was

largely the brahmin pundits and other upper-caste groups who had sole control

over the production and access to knowledge. This is exactly the point that

Jason Keith Fernandes made in his talk The Secret History of Konkani, arguing also that one needs to view the Catholic

Church in Goa, through the intervention of missionaries, as a producer of a

language through the Roman script. Thus, according to this argument, the

Konkani language and knowledge was not destroyed completely but was made

available to a greater number of people.

The colonial legacy of the Roman script

itself is reason enough to reject it as a carrier of authentic Goan and Indian

culture. Such thinking can stray in dangerous directions. For, within this argument,

is the unsaid condemnation of Christianity and Islam, for the destruction of

natives and native culture in the process of proselytizing these religions. As

much of recent work by historians and anthropologists of Christianity and Islam

in the Indian subcontinent has demonstrated, conversion did not necessarily

result in a loss of native culture. Many historians have suggested that

conversion could also be a way out of caste. A perusal of these works would

convince many that the colonial past is a complex history and would need a

deeper understanding than what is allowed by our contemporary political setup.

The argument that English cannot be the

medium of instruction is again a bit suspect. Faleiro’s contention is that the “academic

performance” is not affected if education is imparted in local languages. However,

if one considers his understanding of colonialism and his espousal of the Nagri

script for Konkani, it becomes evident that Faleiro’s arguments have very

little to do with “academic performance”. Several Goan writers have stressed

that the parents should be given the right to decide for their wards. Recently,

a Supreme Court judgment too argued for upholding the choice of the parents in

keeping with the letter and spirit of the Constitution of India. The denial of

English as medium of instruction is also a denial of the legitimacy of the

aspiration of parents for their children. If thousands of parents/guardians feel

that access to English language would provide their wards with greater

opportunities in later life, then we need to consider their point of view much

more seriously, and not brush it aside the way Faleiro does.

We need to start recognizing that the

issues of the Roman script, medium of instruction, and Portuguese colonialism

are not isolated, but are intertwined with each other. This is the reason why,

one can suggest, Faleiro started his speech with a general reflection on the

destruction and mayhem of colonialism and ended with a suggestion for the

organization of “programmes to sensitise parents as to the need for their

children to learn in the mother tongue”. Rather than privileging the diversity

of Goan culture, only certain cultural traditions are privileged and recognized.

In a society that is struggling to maintain its plural and peaceful character,

such thinking will only add to our woes.

(First published in O Heraldo, dt: 1 October, 2014)

See also: 'Supreme Court, MoI, and 'Mother Tongue': Good News for Goa?', here.

'Medium of Instruction in Goan Schools: Mother Tongue or Multitlingualism?', here.

'Battle of the Konkanis: Separating Wolves from the Lambs', here.

No comments:

Post a Comment