Post-colonial Goan

politics has always been about playing the Hindu bahujan against their Catholic

counterparts. Fear of the Hindu bahujan is repeatedly instilled in Catholics

using the bogeyman of Marathi and merger; the Hindu bahujan are constantly made

hostile by falsely stating that the government panders to every Catholic

demand, and by stoking communal sentiments about forced conversions, the

Inquisition, western culture, food habits and so on and so forth. Of course,

both these sections are quite often pitted together against Muslims. In all of

this the hegemony of the Hindu upper-caste is left untouched. This pattern is

amply clear if we look at the Konkani language agitation in the past, and the

present mobilization of the Bharitiya Bhasha Suraksha Manch (BBSM) and RSS,

along with some Marathivadis. Note also the manner in which Nagri Konkani in the

Antruzi dialect (which is the dialect of the Saraswats) is still the official

language of Goa.

The movement by

the Forum for Rights of Children in Education (FORCE) launched in 2011, took a

clear stance against this hegemony. More recently, the issue of replacing the

old idol at the Marcaim temple in Ponda is on the boil, and is rightly termed

as a “Mahajan

v/s Bahujan” issue. Of course the antecedents of these two movements are

not recent. The demand made by FORCE – that of government funding for English

medium primary schools through an act of legislation – can be traced to the

resentment over the imposition of Nagri Konkani as medium of instruction (MoI)

from 1994. The conflict between the “Mahajans v/s Bahujans” also has a history,

with bahujan communities repeatedly trying to gain greater access and control

of the temple properties and management, currently in the control of the mostly

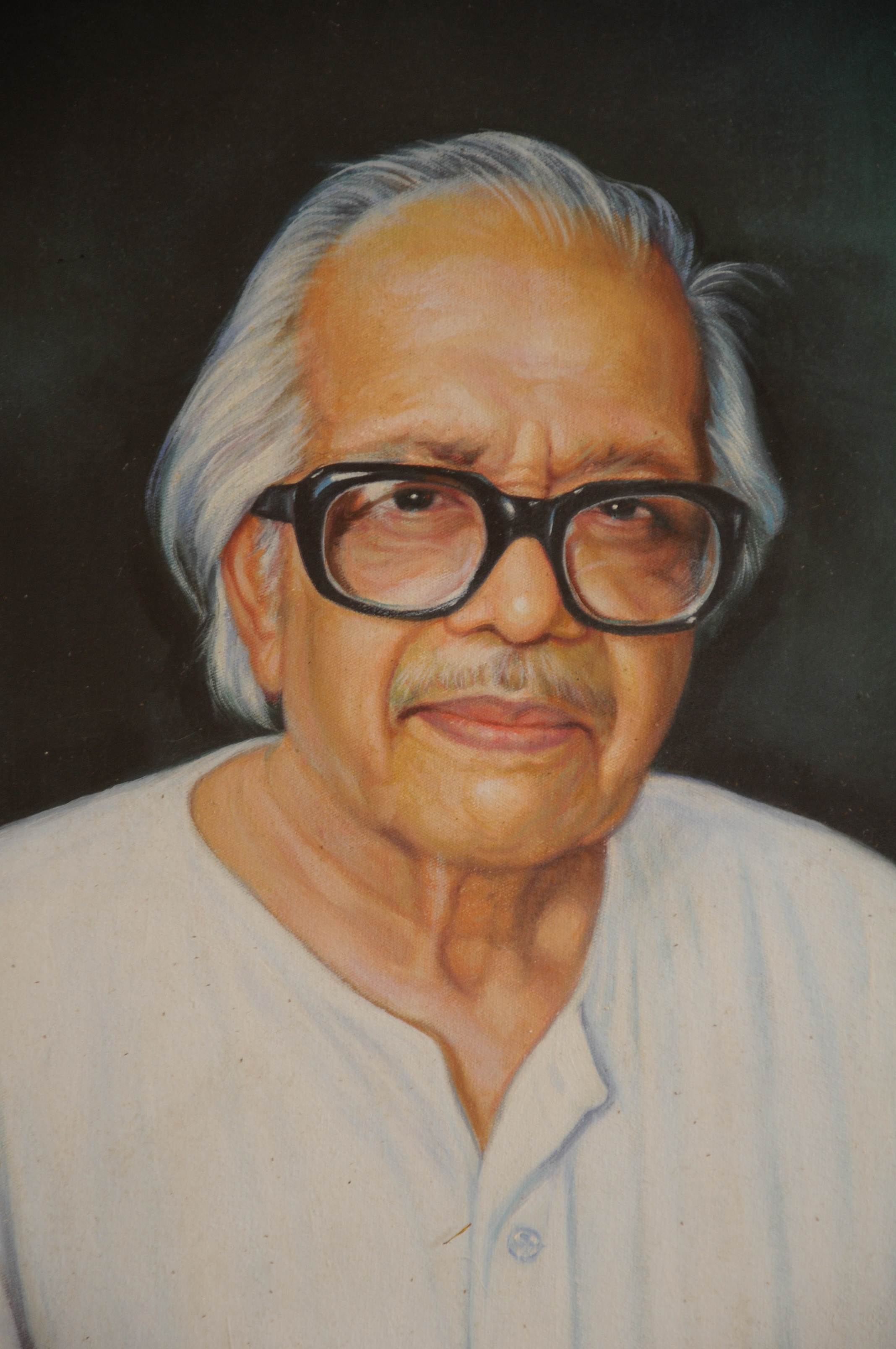

Saraswat Mahajans. The Nagri Konkani writer N. Shivdas, for instance, has been part of movements to gain access to such

brahmanical shrines.

With a judicious

and cautious use of the imagination, if we try to put these two movements

together, it can be argued that it is not just the temples across Goa that are

jealously controlled by Mahajans, but also the ‘temples of learning’ (pardon

the metaphor), thus sustaining their hegemony in Goan public sphere.

Allow me to

explain a bit more. By demanding that the Mahajan Act, or the Regulamento of

1886, be scrapped, the bahujan communities are in effect asking for a greater

control of temple resources, the upkeep of which uses their labour and devotion.

They are asking for the freedom and liberty to exercise their choice of

deciding how the temples are to be run. Similarly, the movement launched by

FORCE is also a movement that demands the freedom and liberty to make a choice

to educate children in the language that the parents deem fit. This choice, as

we all know, is currently held hostage to the irrational and casteist worldviews

and politics of the BBSM-RSS combine – in other words, ‘Mahajans’ of the

temples of learning. Isn’t it after all the futures of bahujan children that are

being held hostage by these ‘mahajans’?

It is a similar

form of power and hegemony that FORCE and the temple movement at Marcaim are

fighting. However, we need to point out and understand some shortcomings within

such movements.

In relation to the

movement spearheaded by FORCE, there are some crucial gaps in their political

mobilization that have come to light. Despite many views asserting

that FORCE’s demands are not just the demands of the Catholic community, FORCE was

cornered into being an organization which represents the demands of Catholics alone.

As O Heraldo’s group editor Sujay Gupta recently observed,

“…when the government was clearly trying to split the movement for rights of all [emphasis added] children by

catering to – or ostensibly catering to – just minority institutions, FORCE

allowed this to happen by not pointing out that the government was trying to

shift the goalposts”. In other words, there was complacency in FORCE’s

mobilization of making more and more allies.

Thus, one can

observe that FORCE failed to sustain a consistent articulation that its demands

are beneficial for the whole of Goa. Although

the bahujan movement at Marcaim does aim for larger political gains beyond the

control of temples, yet these aims are not articulated as such; or at least not

discussed in the Goan press. The ongoing debates only highlight the potential

impact that the Marcaim temple movement could have on the next elections. Limiting

(or allowing to limit) the Marcaim issue or the movement by FORCE to shifts in

electoral politics would mean that we set our eyes on short-term goals. Both

FORCE and the people leading the Marcaim temple movement should think of

themselves as fighting similar ‘Mahajan’ control and hegemony.

In the past, we

have seen some notable – though short-lived – attempts

to unite Catholics and bahujan Hindus through an alliance of the Marathi

Rajbhasha Andolan and Romi Konknni Andolan. Perhaps, the only way lasting

change can be brought about is by a sustained attempt over a number of years to

build solidarity between bahujan interests across religions, that is, assert

universal caste and class interests over other sectarian ones. It is in such

solidarity that the hope for a common, nurturing, and secure society lies.

(First published in O Heraldo, dt: 30 March, 2016)