African gold, ivory, and other riches figure

significantly in Reginald Fernandes’ literary imagination. Though Africa was a

place of unending wealth, it was also simultaneously a place of danger and

adventure within the Konkani romans. The recurrent and frequent references

to Africa were not accidental. There was a particular reason why Africa figured

so prominently in the Konkani romans.

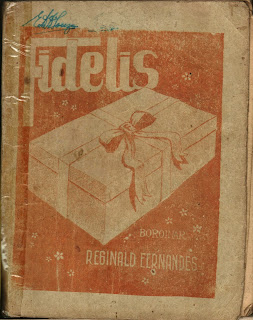

Taking Reginald’s novel Fidelis (1965) as a base, we can address the

issue of the importance of Africa to writers of romans and dwell on the impact it had on the gender

roles process.

The primary reason why Africa featured so prominently

in the imagination of writers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries was due to the large-scale migration of Goans, particularly to East Africa.

As a result, stories about and from that continent had freely circulated in

Goa. The fact of large-scale migration to East Africa is well attested by

Silvia M. de Mendonça-Noronha in her essay, “The

Economic Scene in Goa, 1926-1961” (1990). Mendonça-Noronha states

that emigration “crucially affected the Goan economy throughout the last two

centuries of the Portuguese rule and its impact was very distinctly felt in the

period under discussion (1926-61). Most of the emigrants were Christians,

especially the ones to East Africa. The basic cause of emigration was excessive

pressure of the population on agriculture and the lack of other avenues of

employment, thus giving few job opportunities to the local people. They left to

find jobs for better prospects elsewhere” (p. 282).

Fidelis fits neatly into the abovementioned

pattern of migration to East Africa. The plot opens in Bombay where the hero of

the novel Joel D’Souza is nearly done packing his bags for his journey from

Bombay to Goa the next day. Having completed his studies, Joel is eagerly

looking forward to come back to Goa and to his grandmother. When Joel is about

to go to sleep in the night, he hears someone knocking on his door. On opening

the door, Joel finds a man trying to escape his attackers. It so turns out that

this man is one named Gabriel Pontis, who landed in Bombay from Africa. Fearing

for his life Gabriel hands over a small box to Joel, begging him to deliver it

to his daughter who lives in Goa. Gabriel’s life is in danger as someone else covets

his ancestral wealth that is buried in Gabriel’s ancestral house. The small box

that Gabriel hands over to Joel is the key to this buried treasure, and the

whole novel is a delightful cat-and-mouse chase to possess the contents of the

little box. Thus, as in in real life, migration to East Africa, and the

locations of Goa, Bombay, and Africa are knit together in the novel.

Being from Bardez himself, Reginald would have

witnessed the migration and also would have heard the many stories about Africa

from those who returned to Goa. In a place like Siolim, Reginald’s hometown,

such stories about African wealth were aplenty. Shortly after the much

publicized 101st birth anniversary celebrations, Reginald’s sister-in-law,

Mathilda D’Souza, informed me that he was particularly curious about these

stories emanating from Africa, and would indeed rework them in his novels.

Thus, the stories of Africa circulating in and around Siolim were grist to the

novelist’s writing-mill!

Another important way Africa and migration is

connected with Reginald’s oeuvre is through the absence of father-figures in

the life of the male protagonists in many of his novels. The male protagonist

either has a widowed mother or an ageing grandmother. But on the other hand,

the female protagonist always has a father. It can be suggested that migration

was a cause for the absence of father-figures in Reginald’s novels. In a similar

vein, the portrayal of the male protagonist in Fidelis is no exception. In

this novel, Joel’s father is dead, too!

In the course of a discussion, after the 101st birth anniversary celebrations in Siolim, Joel D’Souza, the Assagao-based journalist who was one

of the main persons in the organization of the celebrations, suggested that

almost every house in Bardez had a person who had migrated to Africa. In particular,

the head of the household would generally migrate to Africa. Though the absence

of the father or father-figure is portrayed through the death of the patriarch

in the novelist’s writing, one can see how the reality of Goa affected by

economic constraints and migration had such a huge impact on the portrayal of

gender roles in Romi Konkani literature that was not confined to the oeuvre of

Reginald.

In the end, one can suggest that the economic reality and

lack of job opportunities which led to migration to East Africa created a

certain template of portrayal of male and female protagonists in Reginald’s

novels. On the one hand, the male protagonist having no father or father-figure

to protect him could be the real hero – a self made man – by dint of his own

strength, sincerity, and a little bit of luck. While on the other hand, the

female protagonist is always in constant need of male protection, though she

exercises her own agency in the choice of her life partner.

While the migration to Africa can be seen as shaping

gender roles in Reginald’s novels, what we can also profitably do is to look at

this corpus of literature to talk about the actual gender roles in Goa,

impacted by this very migration.

For more Reading Reginald, click here.

(First published in O Heraldo, dt: 22 July, 2015)

No comments:

Post a Comment